Each year more than 1.5 million Americans suffer a traumatic brain injury. While the majority of these are minor, some 80,000 to 90,000 patients are left with long-term disability, including paralysis, vision loss, hearing impairment, memory deficits and cognitive behavioral changes. In severely injured patients, death, coma, or a persistent vegetative state may result.

In addition to the more common types of traumatic brain injury, we see a variety of complex injuries at the University of Arizona. These range from severe craniofacial fractures that require a team of neurosurgeons, plastic surgeons, ocular surgeons and otolaryngology specialists to traumatic hydrocephalus, where normal drainage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is blocked and a permanent drain is required. Our subspecialty and multidisciplinary team approach assures that our traumatic brain injury patients receive the best care.

Common Traumatic Brain Injuries

Common injuries include skull factures, contusions, hematomas and hemorrhages.

Skull Fractures

Skull fractures (Figure 1) can affect any part of the cranium, but the convexity or top of the head is most often involved. Skull fractures at the base of the skull usually require significant force and can also be associated with neurologic or vascular injury. For example: fractures through the temporal bone which houses the “inner ear” structures, can produce deafness or facial weakness. Non-displaced fractures are routinely observed. Depressed or complex open skull fractures, especially those with signs that the lining of the brain has been breached, may require surgery to repair the deformity.

Skull fractures (Figure 1) can affect any part of the cranium, but the convexity or top of the head is most often involved. Skull fractures at the base of the skull usually require significant force and can also be associated with neurologic or vascular injury. For example: fractures through the temporal bone which houses the “inner ear” structures, can produce deafness or facial weakness. Non-displaced fractures are routinely observed. Depressed or complex open skull fractures, especially those with signs that the lining of the brain has been breached, may require surgery to repair the deformity.

Contusions

Small contusions or “bruises” on the brain may be associated with some functional impairment, but they usually do not require operative treatment. Instead, drying agents reduce the brain swelling, or surgeons may use a drain placed deep within the fluid spaces of the brain (ventricles) to drain off excess fluid and monitor pressure.

If the patient is found to have a large blood clot on the surface of the brain or within it, surgery may be required to alleviate pressure. If the pressure is severe parts of the brain may be pushed into various skull compartments — an ominous sign that can progress to brain death.

Hematomas

An epidural hematoma (EDH) is located underneath the skull but outside the major lining of the brain. In Figure 2, the large epidural hematoma (arrow) is brighter relative to the brain on CT scan.

An epidural hematoma (EDH) is located underneath the skull but outside the major lining of the brain. In Figure 2, the large epidural hematoma (arrow) is brighter relative to the brain on CT scan.

Epidural hematomas usually result from a skull fracture that tears an artery coursing through the skull. Patients may experience a brief blackout when the injury first occurs and then regain full consciousness. As the blood clot expands they can begin to experience a progressive headache, slip into a coma and even die. However, if they receive prompt surgical care, patients with even the largest EDH can make a good recovery.

A subdural hematoma (SDH) also lies on the surface of the brain, just underneath the major lining (dura). In Figure 3, the large subdural hematoma (blue arrow) compresses the brain on CT scan. The entire brain is pushed over (red arrow) by the blood clot.

A subdural hematoma (SDH) also lies on the surface of the brain, just underneath the major lining (dura). In Figure 3, the large subdural hematoma (blue arrow) compresses the brain on CT scan. The entire brain is pushed over (red arrow) by the blood clot.

Subdural hematomas are often the consequence of tearing veins that run between the brain and its lining. This may occur more commonly in older patients as the brain atrophies and “shrinks” in some areas, making veins more susceptible to injury. If patients take blood thinners, even a small bleed may become massive. In younger patients, more force is generally needed to produce these kinds of injuries. They may also have “bruising” and swelling in the underlying brain.

Functional outcomes in cases of subdural hematomas often depend upon neurological status on arrival at the emergency department: patients with good function going into surgery can expect similar results after.

Hemorrhages

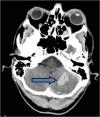

An intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) arises within the substance of the brain. In Figure 4, an intracranial hemorrhage (arrow) in the cerebellum (hindbrain) is shown by CT scan. The smallest of these may represent contusions or “bruises,” while the largest can tear apart normal brain tissue. Although neurosurgeons cannot repair the damage done by the clot itself, removing the ICH through a craniotomy will relieve pressure on the rest of the brain and prevent herniation.

An intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) arises within the substance of the brain. In Figure 4, an intracranial hemorrhage (arrow) in the cerebellum (hindbrain) is shown by CT scan. The smallest of these may represent contusions or “bruises,” while the largest can tear apart normal brain tissue. Although neurosurgeons cannot repair the damage done by the clot itself, removing the ICH through a craniotomy will relieve pressure on the rest of the brain and prevent herniation.

If an intracerebral hemorrhage is the result of trauma, it usually indicates that significant force was imparted to the brain. In severe cases, patients may experience a deep coma or vegetative state as a result. If no large clots or “bruises” are found and if elevated pressure is not found after a drain is placed, surgeons assume the injury is a case of diffuse axonal injury (DAI), in which the severe forces of the trauma shear bundles of nerve fibers deep within the brain and brain stem. Recovery in these cases is variable and slow. Often, these patients will require mechanical assistance with breathing and feeding.